My guest today is Antoine Vanner is author of the Dawlish Chronicles, naval fiction set in the 1870s and 1880s. His latest novel, Britannia’s Gamble, was published last month (October 2017). Royal Navy officer Nicholas Dawlish is a fascinating character, very much in the mould of Hornblower, something that attracted me to Antoine’s novels. The author himself spent many years in international business in all kinds of dangerous places, but now lives more calmly in Britain although he continues to travel extensively on a private basis. His books are published by The Old Salt Press, a New Jersey-based association of writers working together to produce the best of nautical fiction and non-fiction.

My guest today is Antoine Vanner is author of the Dawlish Chronicles, naval fiction set in the 1870s and 1880s. His latest novel, Britannia’s Gamble, was published last month (October 2017). Royal Navy officer Nicholas Dawlish is a fascinating character, very much in the mould of Hornblower, something that attracted me to Antoine’s novels. The author himself spent many years in international business in all kinds of dangerous places, but now lives more calmly in Britain although he continues to travel extensively on a private basis. His books are published by The Old Salt Press, a New Jersey-based association of writers working together to produce the best of nautical fiction and non-fiction.

Welcome back, Antoine. Over to you…

Historical fiction, at its best, is a time machine that transports the reader into another time and place. The best of the genre – such as Steven Pressfield’s Gates of Fire, Zoe Oldenbourg’s Destiny of Fire, David Caute’s Comrade Jacob, Kenneth Roberts’ North-West Passage, C.S. Forester’s Hornblower series – don’t just tell a story but give the actual “feel” of a past era, with its complexities, its concerns, its challenges, its fears and its hopes. In such novels, the styles and construction, and the settings, may be radically different, but all share the characteristic of realism, the impression of a story is being told by an eyewitness who is themselves part of the actual cultural and societal context.

How is this achieved?

I’ve identified below a (non-exhaustive) list of features essential for realism.

Background

- Wide understanding of the social, political, religious and cultural context, as well as of the main events, ideologies and movements of the era. This is the sort of knowledge picked up over years, indeed decades, of reading. 95% of this information is never used specifically but in the writer’s mind it sets the stage on which the story will be played out.

- Accepting that values may be radically different to those of our own time and that even decent people may have had views and attitudes we might regard as repugnant today. High infant and maternal mortality, low life expectancies, surgical procedures that were as likely to kill as to cure, exposure to animal-slaughter, a ruthless-enforced social hierarchy, all fostered a callousness that accepted torture and savage executions in times of peace and that descended into unbounded savagery in times of war.

- Recognising the fog of ignorance that has enveloped much of human history and the fears – and the superstitions – it brought with it. Medicine and technology were based on trial and error, not on reasoned research. The origins of disease were a mystery and, even for intelligent people, witchcraft, astrology and alchemy all seemed to have a rational basis.

- The importance of religion – and especially concern about eternal damnation – is not easy for a modern writer to appreciate. Demonic forces and fear of hell governed many lives and heresy – deviation from orthodox belief, often over abstruse theological issues – was often regarded as treason against the state. The values of the Enlightenment took hold only very slowly, even in sophisticated Western societies, and as the scientific revolution gathered pace in the nineteenth century new insights into the age of the earth and human evolution triggered agonies of conscience for many educated people.

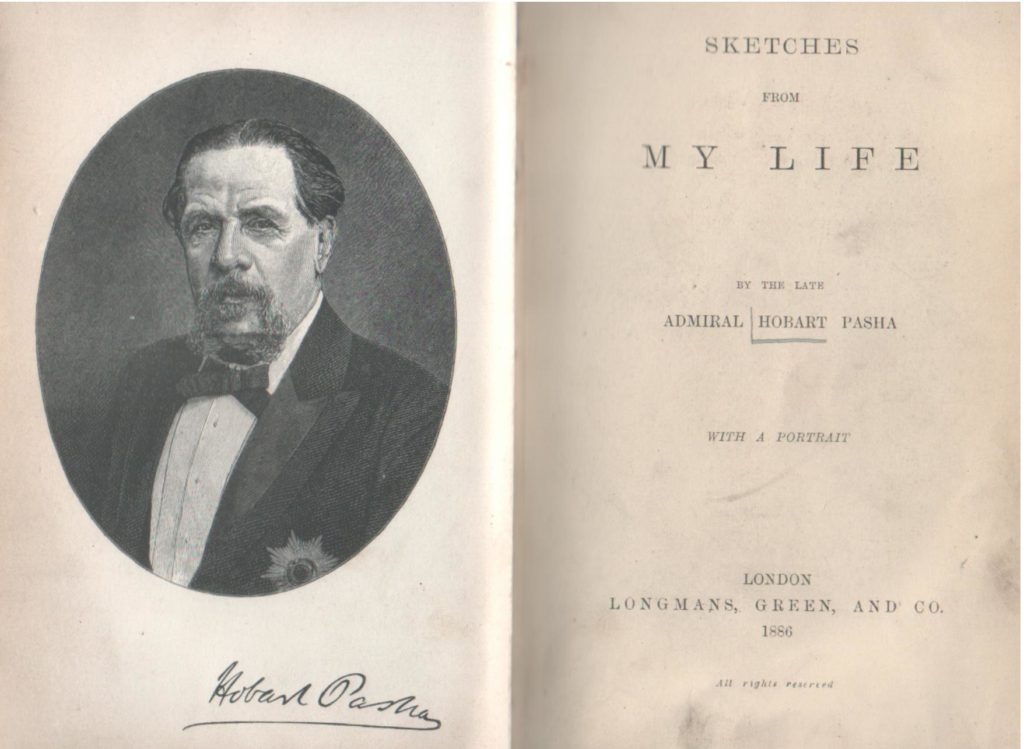

- Wide reading in available contemporary literature is crucial for a writer’s understanding of the ethos of any historical period. The closer that time is to the present, the greater the range available, but the further back one goes the fewer the resources. For me, who writes about the late nineteen the century, there is an embarrassment of riches – Victorians wrote copious and entertaining memoirs – but authors focussing on other eras may encounter appreciable difficulties.

“Feel”

- This involves conveying how it felt, both mentally and physically, to be alive in the past, an experience usually markedly less comfortable than the more cosseted lives we live today.

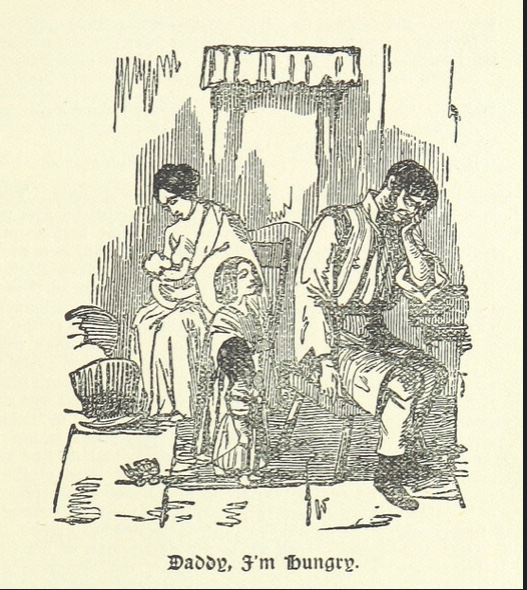

- Bereavement was all but a constant in a world of low life expectancy. A small proportion did live to what we now regard as old age but most families experienced loss of spouses, children or parents at young ages. Marriage was a potential killer for women – frequently a one in six or seven chance of death in childbirth (chance at each confinement multiplied by average number of confinements), as in some African countries today, and many wisely chose life in a nunnery if they could. “Hopping into bed” was a dangerous activity for health reasons as well as for societal-taboos that could be mercilessly enforced.

- Epidemics of communicable diseases were random but frequent, and lack of hygiene was not recognised as a cause, nor were bacterial or viral infection. Outbreaks spread terror, which often triggered persecution of minorities perceived as somehow “other”. The memory of such epidemics cast a shadow of fear for generations to come.

- For much of history, the forces of law, order and governance were remote and inefficient. A high level of violence was accepted as the norm and when the authorities did dispense justice it was frequently with savagery. Desperation and uncertainty in the face of crime and low-level anarchy made vendettas a way of life in many societies.

- The physical reality of daily life was often of endless discomfort – cold and sodden clothing, inadequate footwear, poorly heated houses, squalor and filth, the drudgery of hauling water and chopping wood, lice and vermin, respiratory diseases caused by poor ventilation, malnutrition and poor diet. Fear of famine was seldom absent. When disease struck the king was little less vulnerable than the peasant.

- It is all but impossible to imagine how bereft of human rights so many people have been throughout history and how rigid barriers of class and power inflicted such misery on millions. The greatest tragedy was that, knowing nothing else, they accepted it as normality.

Physical Space:

- “Distance” is a concept that has changed radically over time and, during much of human history, was measured in days rather than in miles. Depending on modes of transport available – including the humble shank’s pony – the perception of distance depended on the state of tracks and roads, on river or canal transport, on the capabilities of open-water shipping. In fiction, whether the journey itself is the story, or merely a transition between one scene an another, the difficulties and duration of travel needs to be credibly represented.

- It’s essential to recognise the impact of seasons on journey times and that winter rains and snow could bring all land transport, and much of commerce and society, to a grinding halt. The same applied to movement by sea and an appreciation of the limitations of shipping – in terms of passenger and freight capacity, ability to harness wind effectively and impact of the arrival of steam technology – is essential.

- Travel speed impacted also on spread of information and days and weeks might pass before news arrived. And once it disappeared over the horizon, a ship was a self-contained and vulnerable world that was lost to all human contact until it docked again. Information-based decision making was a necessarily slow and uncertain process.

- Use of maps, whether they appear in the final book or not, are invaluable plotting tools. Whether on a global or a local scale, and taking account of natural or human obstacles, they allow calculation of travel durations. They may also raise trigger opportunities for plot elements that would not otherwise come to mind. The same applies to maps of towns, villages, campaigns and battles, whether real or fictional.

Hardware

- This term covers not just tools, weapons, vehicles, ships, domestic utensils, surgical instruments and housing but also clothing and uniforms.

- Among readers there will always be experts in one or more of these areas. One error of detail – a button too few on a general’s uniform, a hairstyle that appeared a decade later than in the story’s action, a rifle that actually had a shorter effective range than that at which a hero takes down an adversary – will be enough to destroy credibility. No matter how realistic the remainder of the story may be, a seed of doubt will have been sown.

- The good news is however that this is the easiest type of detail to get right. Not only are myriad written, electronic and illustrative references sources available – including photographs for more recent periods – but in many cases actual artefacts can be seen in museums. Experts in such topics are usually very glad to share information generously and many can be contacted via social media.

Timelines and Real-Life Characters

- Much historical fiction plays out in the context of real events and involves actual real-life characters. In such cases realism makes three demands, as below.

- Except in minor details, the plot’s timeline must dovetail with what really happened.

- At the end of the story the fictional action must not have changed the outcome of history (otherwise it’s the realm of alternative history, another genre entirely).

- Where real-life personages appear, they must behave in character even if whatever the plot calls upon them to do is fiction. Such players also represent a complication as regards refining timelines – if a plot needs George Washington to be attending ball in Philadelphia on the night he was actually crossing the Delaware, then some knowledgeable reader will see the error. From that point on, all sense of realism is lost.

And finally…

The past was different to the present, often vastly so, even if there may be some similarities. People saw the world differently, may have been terrorised by fears that give us little concern and even the genuinely virtuous may have behaved, with clear consciences, in ways that would outrage us today. If this truth is ignored then the resulting historical fiction will be populated by twenty-first century characters kitted out in re-enactors’ costumes.

Good luck to all other historical novelists. I’ve been there, and I am there, and even if it’s hard at times it’s splendid and rewarding fun. Let’s get on with it!

Britiannia’s Gamble – read Antoine’s latest!

1884. A fanatical Islamist revolt is sweeping all before it in the vast wastes of the Sudan and establishing a rule of persecution and terror. Only the city of Khartoum holds out, its defence masterminded by a British national hero, General Charles Gordon. His position is weakening by the day and a relief force, crawling up the Nile from Egypt, may not reach him in time to avert disaster.

But there is one other way of reaching Gordon…

A boyhood memory leaves the ambitious Royal Navy officer Nicholas Dawlish no option but to attempt it. The obstacles are daunting – barren mountains and parched deserts, tribal rivalries and merciless enemies – and this even before reaching the river that is key to the mission. Dawlish knows that every mile will be contested and that the siege at Khartoum is quickly moving towards its bloody climax.

Outnumbered and isolated, with only ingenuity, courage and fierce allies to sustain them, with safety in Egypt far beyond the Nile’s raging cataracts, Dawlish and his mixed force face brutal conflict on land and water as the Sudan descends into ever-worsening savagery. And for Dawlish himself, one unexpected and tragic event will change his life forever…

Britannia’s Gamble is a desperate one. The stakes are high, the odds heavily loaded against success. Has Dawlish accepted a mission that can only end in failure – and worse?

Find out more about Britannia’s Gamble

“Antoine Vanner is the Tom Clancy of historical naval fiction”

Author Joan Druett

Much more on www.dawlishchronicles.com

Follow Antoine Vanner’s historical blogs on www.dawlishchronicles.com/dawlish-blog/

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers INCEPTIO, PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA and INSURRECTIO. The sixth, RETALIO, came out in April 2017. Audiobooks now available for the first four of the series

Find out more about Roma Nova, its origins, stories and heroines… Get INCEPTIO, the series starter, for FREE when you sign up to Alison’s free monthly email newsletter

Great post, Antoine! You’ve hit the various nails squarely on their heads, especially the ones about accepting the past the way it really was and not trying to change or sanitise it to fit current (probably fashion-driven) sensibilities.

I agree William – this is one of the most difficult challenges of all. Possibly the best historical novel I’ve read (and one of my 10 Best of any genre) is Zoe Oldenbourg’s “Destiny of Fire” which enters into a mind set wholly, radically different from our own. It had a massive impact on my own thinking and values, and on what it is to be a human. I fear that movies are even more prone to sanitising than novels. Decade by decade, you can see how movies set in any historical period almost always reflect the cultural concerns and values of the present.

Best Wishes: Antoine

Alison, thanks for hosting this excellent analysis, and huge thanks to Antoine Vanner for taking the trouble to put it all together. Shared on my author page. Thanks again, JGH

It’s a terrific piece, isn’t it? Delighted to have hosted such a comprehensive list by One Who Knows.

I’m glad you enjoyed it Jane. It was interesting writing it – and indeed starting with a mind-map which I used to identify the features that either captivate or repel me in historic fiction. It could have been much longer – but maybe that’ll be for some other occasion.

Best Wishes: Antoine

Fantastic article, Antoine Vanner. It encapsulates all the important points that I believe make good historical fiction. Thank you for posting this, Alison.

I’m glad you like it Simone! One could write an entire thesis on the subject but I trust that I covered the main issues. The question of “feel” is critical but one is never fully sure of success conveying it until feedback comes in from Beta readers! It’s notable that in a wholly fictional alternative universe, Alison manages to give exactly such a feel in her Roma Nova novels.

Best Wishes: Antoine

This is all great advice and common sense, a very clear and concise treatise on the art of historical writing from a master. I leant some new things and remembered so much more I take for granted. Well done.

I have a question though: there are known writers of historical fiction (Walter Scott, Alexandre Dumas, Michel Zevaco, Philippa Gregory) who change a little detail of history to match the plot. This is called usually “writer’s licence/ literary licence” and I knew it was allowed. I admit I have used it in one of my novels too – the Franks/ Normands had sieged Thessaloniki several times, but until 1185 they couldn’t keep it for more than days/ weeks. In my story, a girl from there who left at 14, returns at 21 or so and finds the city still under Frankish occupation, because otherwise her further choice wouldn’t have sense. I think it goes well for the plot. Better than finding her town free… and having the story end there.

A difficult judgement to make. Perhaps you could say that the control of the city switched back and forth between the Franks and the Byzantine Greeks, so it was no surprise that the Franks were in control again when she returned.

Your article validates the sometimes overwhelming task I have set out to complete. It is comforting to know that my “getting lost down research rabbit holes” are actually a necessary–and often pleasantly surprising –aspect of writing in this genre.

Antoine has set it out eloquently and comprehensively and the article is worth re-reading on a regular basis.