My blog guest today is Jane Davis whose first novel, ‘Half-Truths and White Lies’, won a national award established with the aim of finding the next Joanne Harris. Further recognition followed in 2016 with ‘An Unknown Woman’ being named Self-Published Book of the Year by Writing Magazine/the David St John Thomas Charitable Trust, as well as being shortlisted in the IAN Awards, and in 2019 with ‘Smash all the Windows’ winning the inaugural Selfies Book Award. Her novel, ‘At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock’ was featured by The Lady Magazine as one of their favourite books set in the 1950s, selected as a Historical Novel Society Editor’s Choice, and shortlisted for the Selfies Book Awards 2021.

My blog guest today is Jane Davis whose first novel, ‘Half-Truths and White Lies’, won a national award established with the aim of finding the next Joanne Harris. Further recognition followed in 2016 with ‘An Unknown Woman’ being named Self-Published Book of the Year by Writing Magazine/the David St John Thomas Charitable Trust, as well as being shortlisted in the IAN Awards, and in 2019 with ‘Smash all the Windows’ winning the inaugural Selfies Book Award. Her novel, ‘At the Stroke of Nine O’Clock’ was featured by The Lady Magazine as one of their favourite books set in the 1950s, selected as a Historical Novel Society Editor’s Choice, and shortlisted for the Selfies Book Awards 2021.

Interested in how people behave under pressure, Jane introduces her characters when they are in highly volatile situations and then, in her words, she throws them to the lions. The themes she explores are diverse, ranging from pioneering female photographers, to relatives seeking justice for the victims of a fictional disaster.

Jane Davis lives in Carshalton, Surrey, in what was originally the ticket office for a Victorian pleasure gardens, known locally as ‘the gingerbread house’. Her house frequently features in her fiction. In fact, she burnt it to the ground in the opening chapter of ‘An Unknown Woman’. In her latest release, Small Eden, she asks the question why one man would choose to open a pleasure gardens at a time when so many others were facing bankruptcy?

When she isn’t writing, you may spot Jane disappearing up the side of a mountain with a camera in hand.

So let’s find out more…

Can you tell us about the inspiration for your latest novel?

When we moved into the cottage, hanging in the hall was a reproduction of a woodcut depicting Edwardian ladies playing a game of doubles on a tennis court. When we had asked they vendors about the history of the place, they told us that they bought the house from a retired sea captain, who told them it was the gatehouse for the estate. This was certainly the received wisdom in the street, but our cottage was built 100 years after the local manor. Some time after moving in, we joined a guided tour of St Philomena’s manor house, its hermitage and the water tower.

We asked the guide – a local historian – about the possibility that our cottage was a gatehouse for the estate and were told no. But he was intrigued enough to do some research of his own, and what he had to tell us was far more interesting. It was built by a Mr E Cooke as the ticket office for pleasure gardens which opened at the turn of the century. What led a man to embark on such an endeavour after the last of London’s pleasure gardens had failed isn’t written in any history books. It’s clear from Ordnance Survey maps that Mr Cooke didn’t give up on his gardens easily. There was a gradual selling off of plots, the creep of housing, the loss of a stand of trees. My instinct was that something in his past had driven him, something personal, and that same thing that made him so reluctant to let go of his dream. Of course, had our research been more successful, there would have been no story to write.

You seem to flit between contemporary and historical fiction. Is that deliberate?

My life as a writer a whole lot easier if I were to stick to one or the other, but I don’t see a clear dividing line between the two.

My father used to say, ‘I remember when all of this was fields,’ something his father also said to him. For me, the natural progression is to think of my generation who have no memory of fields – not so unusual if you live in London or its suburbs, but I can point to a block of flats and say, ‘This is where my middle school was.’ My interest is change, how it feels personal, as if you’ve been robbed of your memories, and sometimes you won’t even be aware what’s been taken from you until you return to a place you once loved, or were loved in. Somewhere that has acquired more meaning than the place itself. And, returning to that place, you stand there and try to take it in. In Robert Cooke’s case, he sees a sign advertising land for sale, and discovers it is a chalk pit he knew as a boy.

I am now very much aware that my reaction when my father said, ‘I remember when all of this was fields,’ should have been to ask, ‘When was that, Dad? What happened here? What did the fields mean to you?’ But I didn’t ask, and then it was too late to ask because his dementia meant that the words, if not the answers, were lost.

Do you think that writing itself is an act of preservation?

Absolutely. My sister beta read for me and pointed out that I have used a lot of Dad’s favourite sayings in the book. I was totally unaware of this, but I’m not surprised that they crept in. Sometimes writing means bearing witness to a rapidly receding way of life. Sometimes it means resurrecting a piece of the past that has been excluded from history books. During my research I discovered that Mitcham, a town three miles from where I live, was once Britain’s opium-growing capital. There is no shortage of information about the area’s history of lavender-growing, but even though use of opiates was widespread in the nineteenth century, it’s actually quite hard to find information about opium-growing. And so I decided that should be what my main character did for a living.

You’ve talked about your leading man, but can you tell us a little about some of the women in your novel. You have Robert say, ‘Not one of the women in Robert Cooke’s circle is behaving as he expects.’ What did you mean by that?

His wife Freya is speaking her mind, his mother Hettie is taking herself off to Scotland (of all places), his daughters Estelle and Ida are being taught science at school and now he discovers that the winning entry in the competitive he has run for the design of his pleasure garden is the work of a Miss Hoddy.

In Small Eden I wanted to paint a picture of a world on the cusp of change. Following the invention of the steam engine, England changed from a rural, agricultural country to an urban, industrialised country. There were tremendous advances in medicine. In 1853, the Vaccination Act made it compulsory for children to be inoculated against smallpox. The publication of Darwin’s The Origin of Species had people questioning their beliefs. The era saw great building projects, Brunel’s suspension bridges and the Crystal Palace. But despite the fact that there had been a woman the throne since 1837, women had very few rights, and limited access to further education. The aim expressed by the principal of Mill Mount College was to prepare women to become wives, mothers, teachers and missionaries. Another headmistress said that she wanted the character of her school to be ‘delicate womanly refinement’. The Victorian ideal of womanhood was ‘The Angel in the Home.’

I have Robert and Freya’s daughters rebel against that. I have them say, ‘We, the future wives and mothers of England…’ with any number of ridiculous endings, but Robert recognises that they stray very little from the nonsense aimed at young ladies by popular magazines. In fact, it wasn’t just women’s magazines. Respected men in the medical field were adamant that the removal of women from her natural sphere of domesticity to that of mental labour would have a damaging effect on ‘the virility of the race’. Their mother married at seventeen and had four children. Estelle and Ida want more.

Tell us a little more about the mysterious Miss Hoddy.

When Robert decides to run a competition for the design of his pleasure gardens, Florence Hoddy is the only woman to respond. A brilliant mind and a talented artist, but she lost the use of her legs in a road accident, and is cared for by her brother Oswald – a situation that has the local gossips’ tongues wagging. Hiding herself away from pitying eyes, she paints only what she sees from the window at the back of her house. This is where we meet her for the first time.

***

The house they alight in front of is weatherboarded and painted white, a feature that binds the row of cottages and houses together. Each has a distinct personality, some grand, some far humbler, punctuation marks squeezed between established sentences. The winter rose threaded through the trellised porch is well-established, but the doorknocker is a new addition, fashioned in the shape of a fox, complete with head, front legs, paws and tail. Robert knocks, three distinct raps of brass on brass, at the same time looking down at his daughter. His bones cry out when he sees her gold-flecked eyes, so like Gerrard’s.

Though I know not what you are, twinkle, twinkle, little star.

Footsteps and the rattle of a chain. Robert clears his throat. “There’s no need to be nervous. Just be yourself.”

“I’m not at all nervous,” comes her reply.

The door is opened by Oswald Hoddy. “Mr Cooke.” He prods the nosepiece of his spectacles. “And you must be Miss Cooke.” As he looks beyond them to Loax and the photographer, his smile dissolves. “I didn’t realise…”

“I thought the occasion ought to be commemorated,” Robert says.

Mr Hoddy glances over his shoulder. “My sister isn’t accustomed to being photographed.” His voice is low. “Perhaps you’ll give her a little time to get used to the idea.”

Here is clarity. “So your sister is our winner?” Only now that Robert can see the black pinpricks where Mr Hoddy’s beard will break through does he acknowledge the direction his thoughts had taken. Had Miss Hoddy attempted to hoodwink him by disguising herself as a man?

“I simply acted as her surveyor. This moment belongs to Florence and Florence alone. Won’t you come in?”

He stands aside, pointing the way down a corridor so dark and narrow that their arrival at the rear of the house comes as a violent explosion of light. Robert squints, raising a hand to shield his eyes.

“Hello, Miss Hoddy,” he hears Ida say, without waiting for any kind of introduction. “I liked your drawing very much. The cottage especially.”

“Oh, I’m so glad!” The voice within the glare is as clear and bright as the bells that summon the faithful to All Saints.

“Was it from a dream?”

Robert wonders that his daughter can see. All he can determine is an outline, someone seated in front of the window, haloed by the low winter sun.

“I don’t paint dreams, as far as I know.”

That is not quite true. He is beginning to realise that she painted his.

“I draw,” Ida says.

Robert thinks of the spoiled wallpaper. It seems a boast too far for Ida to call her scribblings ‘drawing’.

“And do you draw what you see in your dreams?”

“Sometimes I do.”

“Isn’t it strange that so often we see better with our eyes closed? Logic would have us believe it should be the other way around.”

“Have you drawn many gardens before?”

“Only ours.”

Robert, who has been blinking back his temporary blindness, finds that the white impressions on his retinas are dulling. When he takes down his shield of slatted fingers, Miss Hoddy’s face is turned away from him. It is her neck he notices first, how slender it is, the fine fronds of dark hair escaping their pins.

“It’s very pretty.” A step closer and Ida’s nose will be pressed against the glass.

“It will be prettier still in the summer. If you look, you’ll see it has a lot of paths, so that my brother can wheel me about without causing himself an injury.”

At the mention of wheels, Robert’s eyes flit to Miss Hoddy’s rattan bath-chair. His winner is an invalid.

“Why does he wheel you about?”

“Because my legs don’t work.”

Miss Hoddy’s legs, he sees, are covered by a tartan rug. Little wonder she left the surveying to her brother. Robert, too, seems unable to move, not even to open his mouth and tell his daughter not to stare.

“What happened to them?”

He can remain silent no longer. “Miss Hoddy, I must apologise for my daughter’s forwardness.” His voice is tinged with embarrassed laughter, a father’s indulgence.

Ida turns to him, devastation written on her face. She has done exactly as he asked. She has been herself.

Miss Hoddy reaches for Ida’s hand, as if she has more of a right to it than he. She gives Robert a bold look. “Why apologise?” A fine face, not pretty – her cheekbones are too pronounced for that, her chin too square – but most certainly handsome. Skin, pale in the way of those who spend their days indoors. Younger than himself at a guess, but old enough to be referred to as a spinster. “It was a perfectly reasonable question.” Gently, Miss Hoddy pulls his daughter closer, until she is standing between the chair and the windows, where she tells her, “I had an accident. I was hit by an omnibus and my legs were damaged.”

An image rears up at Robert. Two horses, eyes wild, ears pinned back, whinnying, snorting, panicked. The conductor pitched from his running board into the road. He prays Ida’s imagination is not as vivid as his own.

“Goodness,” Ida says, clearly impressed.

“They tell me I was pulled underneath the wheels.”

Ought this much be said? Freya would be horrified.

“Did it hurt terribly?” his daughter asks, her expression earnest.

“Actually – and you may find this hard to believe –” Miss Hoddy breaks off to laugh, as if she herself struggles “– I have very little memory of the accident. I was visiting friends in Mile End, that I do know.” She tells it as if she’s relating the story of an everyday outing. “We were to have seen a performance of operatic arias.” Miss Hoddy pulls a face and, delighted, Ida giggles. “So I was spared that, I suppose. I remember that a street-vendor was selling Persian Sherbets – I’m rather partial to Persian Sherbets, aren’t you? – so I went to cross the road. I wouldn’t have stepped out without looking, because I was always most particular about crossing the road.”

“The driver took the corner too tightly,” Mr Hoddy says so quietly it can only be meant for Robert’s ears, though his anger is undisguised.

“There was a flash of green and gold, and I have a distinct memory of looking up and seeing an advertisement for Lipton’s Teas. They told me I was unconscious and must have imagined it, but that’s what stuck in my mind. Lipton’s Teas. I was lucky to keep my legs.” She smooths her rug. “They give me no bother. I have no feeling in them.”

Ida’s eyes are wide. “Nothing at all?”

“Nothing.”

“I’m glad they don’t hurt. It’s a very grand chair you have.”

“I call it my chariot. See these handlebars?” Miss Hoddy grips them.

“Yes.” Ida basks in the attention.

“My brother Oswald pushes me, but I steer.”

“Florrie’s in charge.” Time skips forward a second. He calls her Florrie. “Mind you, she always was.” There is pride in Mr Hoddy’s voice.

If, as her title suggests, Miss Hoddy was unmarried at the time of her accident, the chances are she will remain so. Robert looks about the room. Oswald hasn’t mentioned a wife, and there are no signs of children. So this is how they live.Brother and sister. Miss Hoddy was painting before their arrival. The evidence is all about. An easel, her palette, various brushes in jars of milky turpentine, squeezed tubes of oil paints. A useful pastime for someone who spends her life sitting down.

Ida is gripping one of the handlebars. “I should like awfully to try it.”

“Ida, I hardly think –”

Miss Hoddy cuts across him (it is her house, she may do this). “How’s your back today, Oswald?”

Her brother puts his hands to his waist, thumbs pointing to the front of his torso, fingers pressing into the small of his back. “Not too bad, all things considered.”

“Strong enough to push one large person and one smaller person?” She pulls her Paisley shawl tighter.

“I should think so.” Robert sees Oswald discreetly walk to a side table, wrap his hand around a bottle of blue-pigmented glass and pocket it. Laudanum. No doubt he’s strained something.

“It’s high time I took a turn around the garden. You won’t mind sitting on my lap, Miss Ida?”

“If you’re sure I won’t be too heavy.”

“I’d have no way of knowing.” Miss Hoddy gives another laugh. “I suppose it’s very cold outside.”

“Terribly,” agrees Ida.

“Be a dear, Oswald, and fetch my hat. The fur one.” She returns her gaze to Ida. “That way we’ll match. And perhaps I should have another shawl. As for you.” Ida again. “We’ll have to navigate the steps down to the lawn before you climb aboard.”

Believing himself unobserved, Robert turns his attention to the canvas on the easel. It is as if he’s looking out of the window. A sidestep, a slight bend of his knees, and Robert identifies the cyclamen from the foreground of the painting by their dusky pink. He transfers his gaze from the real plant to the painting, back and forth – the detail on the variegated heart-shaped leaves is truly remarkable.

“Well, Mr Cooke?”

Caught out, Robert returns to the purpose of their visit. “What of the prize-giving?”

“Do you know?” The smile Miss Hoddy gives him has a curt quality that might even be disappointment. (Should he mention how much he admires her cyclamen?) “I had quite forgotten.”

——

Thank you so much, Jane. Now I’m not saying this just because Jane is my guest, but Small Eden is a complex and enthralling read. It’s all there: passion, obsession, transition, love, subtlety, rebellion, and all beautifully observed and crafted.

———

Connect with Jane

Website: https://jane-davis.co.uk

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/JaneDavisAuthorPage/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/janedavisauthor @janedavisauthor

Goodreads: https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/6869939.Jane_Davis

BookBub: https://www.bookbub.com/authors/jane-davis

———

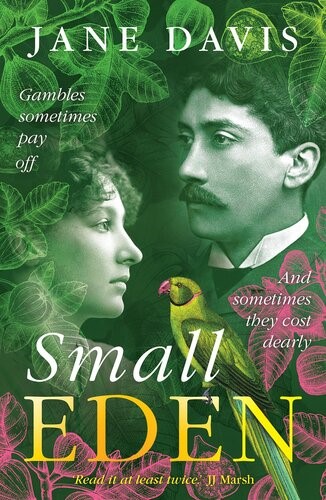

About Small Eden

A boy with his head in the clouds. A man with a head full of dreams.

1884. The symptoms of scarlet fever are easily mistaken for teething, as Robert Cooke and his pregnant wife Freya discover at the cost of their two infant sons. Freya immediately isolates for the safety of their unborn child.

1884. The symptoms of scarlet fever are easily mistaken for teething, as Robert Cooke and his pregnant wife Freya discover at the cost of their two infant sons. Freya immediately isolates for the safety of their unborn child.

Cut off from each other, there is no opportunity for husband and wife to teach each other the language of their loss. By the time they meet again, the subject is taboo.

But unspoken grief is a dangerous enemy. It bides its time.

A decade later and now a successful businessman, Robert decides to create a pleasure garden in memory of his sons, in the very same place he found refuge as a boy – a disused chalk quarry in Surrey’s Carshalton. But instead of sharing his vision with his wife, he widens the gulf between them by keeping her in the dark.

It is another woman who translates his dreams. An obscure yet talented artist called Florence Hoddy, who lives alone with her unmarried brother, painting only what she sees from her window…

Buy the ebook from your favourite retailer: https://books2read.com/u/bPg68r

Paperback currently available from Amazon Amazon UK Amazon US

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series.Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. Double Pursuit, the sequel, is now out!

Find out more about Roma Nova, its origins, stories and heroines and taste world the latest contemporary thriller Double Identity… Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Leave a Reply