I’m delighted to welcome Antoine Vanner, author of the Dawlish Chronicles, for a return visit to the blog. Set in the late Victorian period, the series of naval adventures are linked closely to real historical events, and sometimes personalities, of the period and in most feature a high degree of moral ambiguity and ethical dilemmas.

The settings vary enormously – the Ottoman Empire, Paraguay, Gilded-Age USA, Cuba, Korea, the Sudan and, in the latest book, East Africa. The period is one of unprecedented social, political, scientific and technological change and the first cracks are appearing in Britain’s position as a leading power. Old animosities with France and Russia persist, Germany, Japan and the United States are emerging as major players.

This is the world in which the Royal Navy officer Nicholas Dawlish (1845-1918) and his formidable wife Florence (1855-1946) must fight for career advancement and social acceptance while still retaining their integrity.

Over to Antoine!

Writing the opening sentence of any novel is likely to be more difficult than producing an entire chapter later. For his masterpiece, The Go-Between L.P. Hartley crafted a superb sentence that has become one of the best known in modern literature, so much so that many who quote it do not know its origin.

“The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.”

It’s more than a book opening – it should be the motto, the guiding light, the dictum that anyone writing historical fiction should constantly have in mind. It is also however a truth honoured more in the spirit than in the letter. Ignoring it results in novels which are little better than pastiches, pageants populated by twenty-first century characters clad in re-enactors’ costumes and motivated by twenty-first-century values and attitudes.

For the past is indeed a foreign country, even if that past is as recent as the lives of our deceased parents or grandparents. L.P. Hartley’s narrator knows this – he’s an old man, looking back to the England he knew when he was thirteen years old.

It’s not just a question of external detail – writers, like re-enactors, often agonise over achieving absolute accuracy as regards clothing, weapons and everyday articles – for unless the characters’ mindsets are consistent with the values and beliefs of the era portrayed the story will never be convincing.

And those mindsets can be very uncomfortable to enter into

There’s somewhat of a paradox here. It’s not too difficult to achieve realism when portraying psychopathic tyrants or villains – their actions are the embodiment of their malignancy. It’s far harder to admit that a virtuous and admirable individual, whether actual or fictitious, can have held beliefs or values which we find repugnant today, and that they saw nothing wrong, and that it was even admirable, in acting in accordance with them. Seen through the lens of the early twenty-first century – a lens that will itself change significantly in the decades to come – the world-views and preoccupations that governed our ancestors are difficult to comprehend and harder still to reflect in fiction.

Instances abound from every era of history but it’s as good an example as any to take the Early Modern period, say 1450 to 1650. Portrayal of characters in fiction set in this time must take account of the belief of the Devil as an active player in human affairs, often physically manifest, and of hellfire and eternal damnation as appropriate punishments for holding views considered in any way heretical. Regardless of whether regions were dominated by Catholics, Lutherans or Calvinists, the division between temporal and religious authority was blurred, and sometimes non-existent. Persecutions, hideous tortures, massacres, witch hunts and imposition of social control at levels comparable to those in twentieth century totalitarian states, all followed. For a major portion of most populations these measures were considered fully justifiable, even praiseworthy, while for those whose questioning could be regarded as what Orwell later describe as “thought crime” the penalties could be extreme – and seen by most as well justified.

The believers, fervent or otherwise, were not necessarily evil people but they were complicit in crimes as massive, for example, as the witch hunts that were estimated to have between 40,000 to 60,000 lives in Europe in the 15thand 16thCentury. Nobody was safe from accusations of witchcraft and the fact that the scientific revolution was beginning helped little. Johannes Kepler (1571-1630), the mathematician and astronomer who discovered the laws of planetary motion, spent fourteen months defending his imprisoned mother against the charge of being a witch. This would have ended in her burning had he not been successful – a textbook example of state-sanctioned superstition confronting the earliest stirrings of the still far-off Enlightenment.

Any fiction written about this period needs to face the fact that people who were considered moral – or even enlightened – by the standards of their own day, lived in a climate of fear, not just about the here and now, but about all eternity. To cope with that, they countenanced, supported or actively implemented controls, including torture and savage execution, which one would have thought repugnant to any rational or compassionate human being at any time in history. And yet by their own lights these people saw themselves as decent and upright.

The modern novelist’s dilemma

I encountered the problem of getting into the mindsets of a wholly different era when writing my own most recent novel, Britannia’s Mission, the seventh of the Dawlish Chronicles series. Writing as I do about the late nineteenth century, I am always faced with such challenges. In this book however, set in East Africa in 1883, in which the protagonist, the Royal Navy Captain Nicholas Dawlish, must deal with both Catholic and Protestant missionaries, the task was especially daunting. Having lived for many years in Africa I was aware of the massive impact such missionaries had in Sub-Saharan Africa in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an impact that is still important today. Selfless, indomitable, sometimes naïve but always heroic, often to the point of madness, these missionaries were responsible for the fastest and largest mass-conversion in history. Anyone familiar with contemporary Africa cannot but be impressed by the exuberance and sincerity of the Christianity that flourishes there in so many forms and how integral it is in community life. It is touching also to see how often the memory of missionaries long dead is still revered. But when I came to research these heroic – though somehow forbidding – people in more detail for my book, reading biographies or memoirs, identifying hymns written expressly for the mission field, I was struck by how greatly different they were in thought and behaviour to myself and my contemporaries, even to those of strong religious convictions.

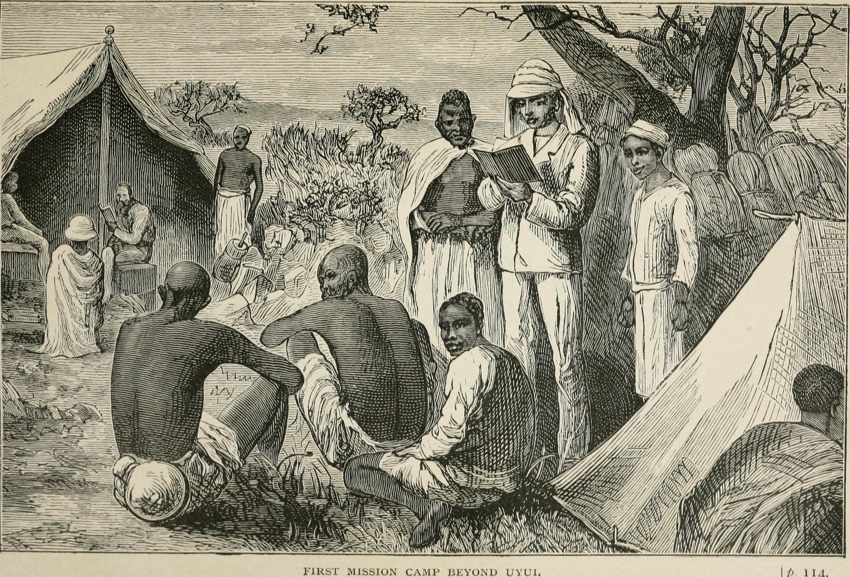

The idealised Victorian ideal of a missionary in Africa – the actuality was considerably less pleasant (Mackay of Uganda). Public domain

The missionaries’ legacy

Judged by today’s standards, such 19thCentury missionaries are easy to caricature to the point of ridicule, but they left a legacy not only in the field of religious belief but in medical care, education and raised awareness of the value of human life. Whether poorly educated, as were so many of the men and women from humble backgrounds who volunteered to meet challenges they could barely imagine beforehand – and such people feature in Britannia’s Mission – or representatives of better-funded undertakings by well-established religious bodies – who also feature – they cheerfully accepted the risk of death by violence or disease and the certainty of long years of privation or loneliness. Within the context of a novel of naval adventure, whose other main themes include suppression of the slave trade and the emergence of Imperial Germany as an aspirant colonial power, and featuring conflict on land and on water, I hope that I have done these missionaries justice by the standards of their own time.

And that’s perhaps what we need to aim at in historical fiction. For the past is indeed a foreign country…

Thank you, Antoine. Such strong belief is often difficult for a modern audience to understand, but you have provided a nuanced background to the missionaries’ activities as well as the challenges of writing about them. Currently enjoying this latest Nicholas Dawlish adventure!

What’s Britannia’s Mission about?

1883: The slave trade flourishes in the Indian Ocean, a profitable trail of death and misery that leads from ravaged African villages to the insatiable markets of Arabia. Britain has been long committed to the trade’s suppression but now a firebrand British preacher is pressing for yet more decisive action. Seen by many as a living saint, but deliberately courting martyrdom, he is forcing the British government’s hand by establishing a mission in the path of the slavers’ raiding columns. His supporters in Britain cannot be ignored and are demanding armed intervention to protect him.

1883: The slave trade flourishes in the Indian Ocean, a profitable trail of death and misery that leads from ravaged African villages to the insatiable markets of Arabia. Britain has been long committed to the trade’s suppression but now a firebrand British preacher is pressing for yet more decisive action. Seen by many as a living saint, but deliberately courting martyrdom, he is forcing the British government’s hand by establishing a mission in the path of the slavers’ raiding columns. His supporters in Britain cannot be ignored and are demanding armed intervention to protect him.

This ostensibly simple task is assigned to Royal Navy Captain Nicholas Dawlish and the crew of the cruiser HMS Leonidas. But this new mission quickly proves that it’s not going to be as straightforward as it seemed back in Britain . . .Two Arab sultanates on the East African coast control access to the interior. Overstretched by commitments elsewhere, Britain is reluctant to occupy these territories but cannot afford to let any other European power do so either. And now the recently-proclaimed German Empire is showing interest in colonial expansion, and its young navy is making its appearance on the world stage . . .

“Antoine Vanner is the Tom Clancy of historical naval fiction” – Author and nautical historian Joan Druett

Watch a video in which Antoine discusses Britannia’s Mission!

Connect with Antoine:

The Dawlish Chronicles: https://dawlishchronicles.com

Twitter: @AntoineVanner https://twitter.com/AntoineVanner

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/DawlishChronicles/

All seven (to date) Dawlish Chronicles are available in paperback or kindle formats – and subscribers to Kindle Unlimited and Kindle Prime can read them for no extra charge. Click here for details: https://amzn.to/2PlEraR

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, INSURRECTIO and RETALIO. CARINA, a novella, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories, are now available. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. NEXUS, an Aurelia Mitela novella, will be out on 12 September 2019.

Find out more about Roma Nova, its origins, stories and heroines… Download ‘Welcome to Roma Nova’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email newsletter. You’ll also be first to know about Roma Nova news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

I have used “the past is a foreign country” line for many years with my students in discussing the writing of history (let alone historical fiction). Until this blog I had no idea of the origin of the line, however. Thank you Antoine and Alison. It is flatly ridiculous to try and apply modern sensibilities and attitudes to the past, either in fiction, or non-fiction. A good example in the US at the moment is retro-actively applying the “Me too” approach to the relationship between Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemmings. The fact is we have *no* idea what that relationship was, and accusing Jefferson of continuous rape over a 20 something year period is simply unsupportable. Or discovering that some 19th century figure was a racist, and therefore persona non grata. With some notable exceptions pretty much everybody was a racist in the 19th and well into the 20th centuries. I could go on, but I think I’m starting to announce the obvious.

It’s the proverbial minefield, Charley!

In my own recent collection of short stories, the first one took place in AD 370 in Roman Noricum. A young tribune, a member of the military and aristocratic elite, didn’t even think twice about commandeering what seemed a local peasant girl for his sexual pleasure. Now as a 21st century feminist, that’s not behaviour I would expect today, but that’s how it was then.

Of course retribution came to him in an unexpected way… 😉

Hello Charley:

Your points are 100% valid. “The Good People in Bad Times/Regimes” represent one of the worst dilemmas anybody can be confronted. It was one of the main themes in my novel “Britannia’s Reach”.

The most perfect exposition of these themes I’ve ever read is in Zoe Oldenbourg’s masterpiece “Destiny of Fire” – it had a massive and permanent impact on my own views on value of life as I witnessed an incident not unlike those in the novel just two months after first reading it in 1974. Oldenbourg, more than any other author I know, enters fully into what must be a very close approximation of the medieval mindset. It’s a terrifying work and I’ve read it several times since (All her otehr works are of similar quality).

As regards L.P. Hartley’s “The Go-Between” its also worth watching the Julie Christie – Alan Bates movie of it from about 1971. Other than John Huston’s “The Dead” (Joyce’s perfect short story) I know of no other movie adaptation that is so close to the orignal and a great piece of cinema to boot. Best Wishes: Antoine