Rudolf Rassendyll (Sigh)

Princess Flavia (Aaah!)

Duke Michael (Grrrr!)

Rupert of Hentzau (Wow but grr!)

When I picked up The Prisoner of Zenda at age 12, I was enraptured. It was a torch under the bedclothes job. When it ended I cried, partly from the denouement, partly because it had finished. You know that sense of deep loss when you say goodbye to beloved characters.

Then I discovered Rupert of Hentzau. Thank the gods. I was plunged back into the thrills, romance, courage and sacrifice of Ruritania. And the high moral choice of the hero and heroine.

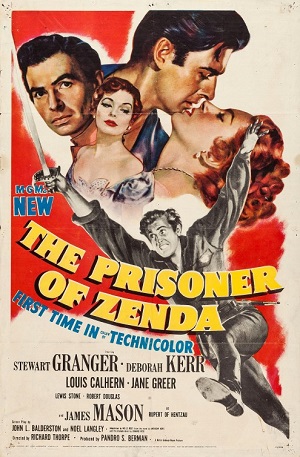

The stories set between the 1850s and 1880s have been updated and revised; they’ve been made into a BBC television series and feature films, notably the one starring the fabulous Stewart Granger, but what’s between the covers still grabs my mind and emotions.

Ruritania itself is an imaginary country in central Europe, a ‘placeholder kingdom’ and is used in academia and the popular mind to refer to a hypothetical country. The author, Anthony Hope, depicts Ruritania as a German-speaking Catholic country under an absolute monarchy, with deep social, but not ethnic, divisions reflected in the conflicts of the first novel, The Prisoner of Zenda.

Ruritania itself is an imaginary country in central Europe, a ‘placeholder kingdom’ and is used in academia and the popular mind to refer to a hypothetical country. The author, Anthony Hope, depicts Ruritania as a German-speaking Catholic country under an absolute monarchy, with deep social, but not ethnic, divisions reflected in the conflicts of the first novel, The Prisoner of Zenda.

Hope’s novels resulted in ‘Ruritania’ becoming a generic term for any small, imaginary European kingdom used as the setting for romance, intrigue and the plots of adventure novels. It even lent its name to a whole genre of writing, the ‘Ruritanian romance’.

Such stories are typically centered on the ruling classes, almost always aristocracy and royalty, or as in Winston Churchill’s novel Savrola the dictator in the republican country of Laurania who is overthrown. The themes of honour, loyalty and love predominate, and the works frequently feature the restoration of legitimate government after a period of usurpation or dictatorship.

The genre has been much spoofed, mined and copied: GB Shaw’s Arms and the Man, Dorothy L Sayers’ Have his Carcase and Nabakov’s Pale Fire parody elements. In the satire The Mouse That Roared, the Duchy of Grand Fenwick (the title role played by the brilliant Margaret Rutherford) attempts to avoid bankruptcy by declaring war on the United States as a ploy for gaining American aid.

The genre has been much spoofed, mined and copied: GB Shaw’s Arms and the Man, Dorothy L Sayers’ Have his Carcase and Nabakov’s Pale Fire parody elements. In the satire The Mouse That Roared, the Duchy of Grand Fenwick (the title role played by the brilliant Margaret Rutherford) attempts to avoid bankruptcy by declaring war on the United States as a ploy for gaining American aid.

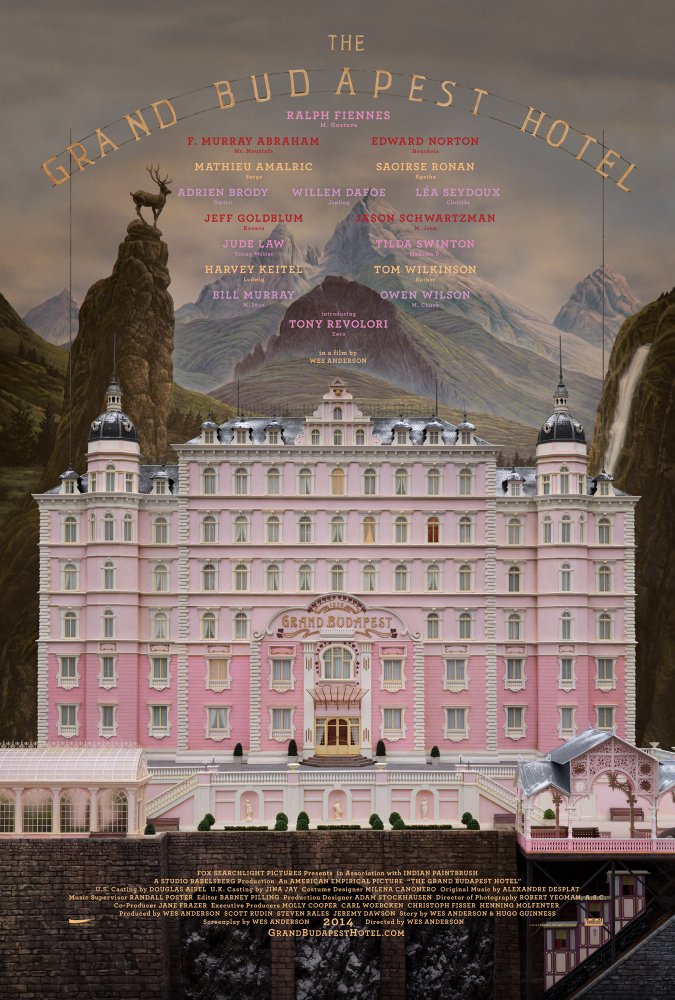

Sci-fi writer André Norton borrowed many elements and Ursula K. Le Guin set a number of short stories and a novel in the fictitious and essentially Ruritanian East European land of Orsinia. The Grand Budapest Hotel, a 2014 comedy film is set in the fictional nation of Zubrowka, a central European alpine state teetering on the outbreak of war.

Why does the idea of Ruritania persist and why do the books still attract readers?

Let’s unpick the themes behind the stories…

– There’s romance – the heaviest read genre on the planet – and the ‘world lost for love’ vs. ‘love lost for the world’ conflict

– Thrills, tension, mixed motives, dark plots and evil schemes, turning the screw on our emotions

– And as for action adventure, apart from the storyline of the books, there are chases, sword fights, gun duels, escape by night, dungeons and secret stairways

– The ‘noble Englishman’ idea which we may think is dead – I suggest Jonathan Pine in The Night Manager or even our old friend James Bond keep this one on the front burner

– Exaggerated nature of fictional characters who can be more noble or dastardly than we are

Of course, Ruritanian stories have to be plausible by having a good number of connections to our world while maintaining that essential difference, and they have to be consistent within their own world. Nobody likes being jolted out of a fictitious world by sloppy writing.

Now, there are plenty of imagined other worlds, often projecting an existence hundreds or thousands of years in the future or one here on Planet Earth, but after a massive disaster. Both can be pretty grim. But do alternative existences have to be dystopian or post-apocalyptic to be authentic?

Enter Ruritania. The stories are hopelessly old-fashioned, somewhat sexist and rather naive, but they are essentially optimistic. But more than anything they are an escape from the dullness and stress of everyday and emphasise the good guys winning in a morally acceptable way.

Roma Nova is a world away from Ruritania but it does use its core concepts of adventure, romance, honour and taking tough moral decisions. While its stories are set in a small European country, the small state’s Roman-ness, intense struggle through history and egalitarian social system separate it from Ruritania, making it unique, possibly the centre of a new genre even?

While often patrician, Roma Nova’s characters are more fallible, yet more robust and are ready to step over any moral line set by Anthony Hope.

They would eat Rupert of Hentzau for breakfast.

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers.

Find out more about Roma Nova, its origins, stories and heroines and taste world the latest contemporary thriller Double Identity… Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email newsletter. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Oh, one of my favourite books and films…dastardly James Mason and devilish handsome Stuart Grainger. Thank you for the reminder and analysis.

I’m reading some of his lesser well-known stories such as The Heart of Princes Orsa. Old-fashioned, of course, but very vivid.

One of the few movies I’ve ever seen which was both true to the book and equally good. Best duel EVER.

Even better duel than the one in Zorro!

All the ingredients of a great historical romp. No wonder you still love it.I am tempted…

Worth being tempted, Paula!

Oh yes, I read them both when i was about 12 s well. I read them over and over. Along with books like The 39 Steps, She and King Solomon’s Mines. Loved them all.

Sounds as if your and my reading tastes coincide! There’s nothing quite like a bit of adventure fiction, is there?