In the past year in the UK, there has been a lot of talk on the news about “plebs”. I’m not offering any comment on that, but listening to media reports and reading social media gossip, I started to wonder if people knew where the terms came from. Ah! It’s those pesky Romans again. So here’s a blaggers guide…

In the past year in the UK, there has been a lot of talk on the news about “plebs”. I’m not offering any comment on that, but listening to media reports and reading social media gossip, I started to wonder if people knew where the terms came from. Ah! It’s those pesky Romans again. So here’s a blaggers guide…

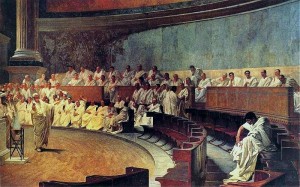

First, the caveat: “Rome” lasted 1229 years and the roles, power, responsibilities, ranks and privileges fluctuated over that long period which ran from the Regal era, Republic, Principate, Dominate and into Late Antiquity, so this guide is a general one.

First, the caveat: “Rome” lasted 1229 years and the roles, power, responsibilities, ranks and privileges fluctuated over that long period which ran from the Regal era, Republic, Principate, Dominate and into Late Antiquity, so this guide is a general one.

Basically, there were two main classes of free citizens in ancient Rome – the patricians (aristocrats) and the plebeians (everybody else). Equites, often called knights, formed a band of mid-level aristocrats ranking below the patricians.

Patricians: upper class, the nobility and wealthy land owners, often senators (law-makers), governors, senior magistrates, advisors to the emperor. Augustus introduced n a new rule that senators had to have property worth 1,000,000 sesterces. Senators were also not allowed to become directly involved in business – particularly shipping or government contracts where there might be a conflict of interest. Given they were also unpaid, this meant that only a small percentage of the population could afford to become deeply involved in politics.

Equites: middle-ranking, provided senior administrative and military officers and came to dominate mining, shipping, manufacturing industry and tax farming. Later, they included leading non-Italian families who rose to prominence, such as emperor Vespasian.

Plebeians: everyone else in ancient Rome from well-to-do tradesmen all the way down to the very poor. Shopkeepers, crafts people, merchants and skilled or unskilled workers might be plebeian. From the 4th century BC or earlier, some of the most prominent and wealthy Roman families, as identified by their gens name (nomen), were of plebeian status. Literary references to the plebs, however, usually mean the ordinary citizens of Rome as a collective, as distinguished from the elite. In the very earliest days of Rome, plebeians were any tribe without advisers to the king. In time, the word came to mean the common people. Plebeians were excluded from becoming magistrates or entering religious colleges, and they were not permitted to know the laws by which they were governed. Plebeians served in the army, but rarely became military leaders.

Dissatisfaction with the status quo occasionally mounted to the point that the plebeians engaged in a sort of general strike, a secessio plebis, during which they would withdraw from Rome, refusing to fight and leave the patricians to face the enemy by themselves. From 494 to 287 BC, five such actions during this “Conflict of the Orders” resulted in the establishment of plebeian offices (the tribunes and plebeian aediles), the publication of the laws (Twelve Tables), the establishment of the right of plebeian-patrician intermarriage (Lex Canuleia), the opening of the highest offices of government and some state priesthoods to the plebeians, and legislation (Lex Hortensia) that made resolutions passed by the assembly of plebeians, the concilium plebis, binding on all citizens.

Social mobility

During the Second Samnite War (326–304 BC), plebeians who had risen to power through these social reforms began to acquire the aura of nobilitas, “nobility”, marking the creation of a ruling elite of nobiles that allied the interests of patricians and noble plebeians. From the mid-4th century to the early 3rd century BC, several plebeian-patrician “tickets” for the consulship suggests political cooperation between the classes. Although nobilitas was not a formal social rank during the Republican era, a plebeian who had attained the consulship was regarded as having brought nobility to his family. Such a man was a novus homo, a “new man” or self-made noble, and his sons and descendants were nobiles. Marius and Cicero are notable examples of novi homines in the late Republic, when many of Rome’s richest and most powerful men—such as Lucullus, Crassus, and Pompey—were plebeian nobles.

Some or perhaps many noble plebeians, including Cicero and Lucullus, aligned their political interests with the faction of optimates, conservatives who sought to preserve senatorial prerogatives. By contrast, the populares or “people’s party”, which sought to champion the plebs in the sense of “common people”, were sometimes led by patricians such as G.Julius Caesar and Clodius Pulcher.

Straightforward, isn’t it? But I hope I’ve shed some light on the origin of plebs and patricians.

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, INSURRECTIO and RETALIO. CARINA, a novella, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories, are now available. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. NEXUS, an Aurelia Mitela novella, is now out.

Download ‘Welcome to Roma Nova’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email newsletter. You’ll also be first to know about Roma Nova news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.